Introduction

You can find his works in barrios of Nicaragua and among the remnants of bombed down Baghdad, inside self-governed communities of Ulster and public libraries in the US and UK. Images created by this wonderful artist address to workers and students from the walls of many towns and cities. And many of these images have clear political messages.

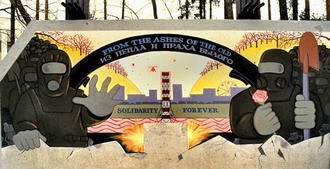

Professor Mike Alewitz – American muralist and activist of workers’ movement worked also in Ukraine. He took part in the project dedicated to the 10th anniversary of Chernobyl disaster that was held in the town of Slavutich in 1996.

‘From the ashes of the old we will build a new world’ – these words from the IWW song ‘Solidarity forever’ are the motto of ‘Chernobyl works’ created by Mike Alewitz. However, while working in Ukraine Mike Alewitz faced with our officials who tried to make obstacles to the work of the artist.

As Paul Buhle, American labor culture historian writes in the book ‘Insurgent images’ devoted to the art and work of Mike Alewitz: “City officials in the new, post-meltdown district near Chernobyl greeted Alewitz so cheerily, wined and dined him so continuously that he became suspicious. Sure enough, they were hoping distract him by using up all of his time in the Ukraine because of their concern that his drawing (of workers in protective gear) actually suggested that nuclear power had safety problems!”

But then – 10 years later – organizers of the Kiev festivals of social graffiti ‘Colours of protest’ devoted their fests to Mike Alewitz.

Alewitz was named a Millennium Artist for the White House Millennium Council in 1999. The artist wished to create the image of Harriet Tubman – American abolitionist – heroine of the Afro-American struggle against slavery – she organized guerilla groups that liberated slaves. When his original design—Tubman armed, overturning a slave ship on one side and a sweatshop on the other side—was rejected, Alewitz was asked by the press if he would remove the gun. He refused to do so.

Mike Alewitz’s ‘Gun’ – Mostly Colours

As Martin Sheen, outstanding American actor who played leading role in ‘Apocalypse now’ said about artist: “Mike Alewitz’s art has given eloquent voice to the aspirations of working people throughout the world. His heroic figures and vibrant colors are powerful weapons in the hands of the oppressed.”

Some of his works shared the fate of well-known mural of Diego Rivera created in Rockefeller’s Centre. However, soon other images including Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Marx an Engels, Joe Hill and Emiliano Zapata addressed to workers and students from the walls and banners.

Rebellious workers, Los Angeles riots, Sandinistas- rebels – scenes and images created by Mike Alewitz on the walls and union banners should enlighten and inspire the viewer to fight against capitalism. Besides, the very process of creation should teach solidarity and collective work. While working Mike Alewitz involves in process other artists and people from local community, students and workers as well. As the artist-activist, Alewitz asserts: “My work is more than images. It is about the theater surrounding the creation of the piece”.

The Chronicle of Higher Education writes in review of the book devoted to the Mike Alewitz’s art: “Alewitz’s approach is ideally suited to the postmodern and post-state socialist era, when everything rebellious must be created anew and when ‘culture’ along with ‘labor’ are urgently needed to salvage a world from eco-disaster, perpetual war, and the plundering of human possibility.”

Although recently some western artists turn to the traditions of the early soviet agitprop art just because it’s one of the ways to shock public and step over some taboo, but for Mike Alewitz his art was always closely connected to his political activity as an organizer and activist of protest movements of workers and students.

Mike Alewitz has kindly agreed to give an interview for our site ‘Liva’ and we propose it to the attention of our readers.

- Could you tell us, please, why do you decided to dedicate your talent to the political agitation and workers’ solidarity?

Like many of my generation, I became radicalized primarily around the issue of the war in Vietnam and opposition to racism. I was a student leader at Kent State University, chairman of the antiwar coalition, when the massacre of May 4, 1970 took place. I was an eyewitness to the shootings and a leader of the national student strike that followed the invasion of Cambodia and the shootings at Kent and Jackson State.

I was also a socialist activist - I remain a revolutionary Marxist to this day, though I am not a member of an organized tendency.

I spent many years working as an organizer for the antiwar and socialist movements. I also worked in industry in order to be active in unions – I was a railroad laborer, a machinist, a union sign painter, etc. Today I am a member of the scenic artists union and the professors union.

I went to art school when I was older, and my art is an outgrowth of a life of activism.

- Could you tell us how and when at first you was impressed by the works of soviet avant-garde of 1920’s? Do you consider them still relevant for agitation? What particular artists have inspired you?

Although I work primarily as a muralist, my work is more in the tradition of the Soviet agitprop artists than the Mexican muralists. My work is utilitarian – meant to be used as part of the strikes and struggles of working people. It is not meant to be an enduring object of beauty, such as the murals of Rivera or Orozco.

Of course, I am very inspired by the Mexican muralists, as well as a broad range of soviet artists including Tatlin, El Lizzitsky, Popova, Mayakovsky, Rodchenko, Stepanova, etc.

I consider the early years of the Russian Revolution to be a critical chapter in the development of art. This history has largely been suppressed and needs to be relearned as part of the conquest of knowledge by our class.

- The Art (in general) is it mostly for you a weapon in class struggle or has some other aims too?

I am in agitprop artist, but I do not believe that this approach is necessarily for all artists. Each artist must find his or her own voice. For some that may mean a very personal, abstract or formal type of art.

However, I think that all artists, regardless of their means of expression, should be conscious of the struggle of humanity to overcome the horrors of capitalism. That is what informs all great art, whether it is overtly political in its imagery or not.

In my home, I would much rather have a Cézanne hanging on my wall to look at, then one of my agitprop murals!

- When you worked for Chernobyl project, do you remember your impressions of our country? What especially impressed you in this post-Soviet republic?

My time in the Ukraine was a great learning experience. Being at Chernobyl was at times quite surreal and gave me an appreciation of how Stalinism played such a critical role in destroying the creative and spiritual life of the working class.

But when the workers refused to be silenced, after the old apparatchiks tried to stop our project, I saw an amazing courage displayed that gives me great optimism for the future of the Ukraine. They went to a cement factory, built two walls, brought them to the center square of Slavutich, and installed them for me to paint–all in defiance of the government!

- How often have you faced with censure in your activity? In what countries? And what particular images, symbols or scenes are usually being censored.

As far as I know, I am the most censored artist in the world. But you will never read about me in the art press for a very simple reason: when you create art with workers, you are no longer considered part of the art world. The ruling class does not care if you use workers as subjects, as long as you remain safely ensconced in the gallery system.

I have had my work censored and destroyed by employers, universities, union bureaucrats, educational institutions, and radical organizations.

Art - the genuine expression of working people - is instinctively hated and feared by the authorities. It is not so much a matter of particular images, it is the rebelliousness represented by a willingness to make public statements through art. That is why there is a war that is directed against graffiti and street artists. It isn’t that the images are necessarily political, it’s that they think workers should shut up and get back to their workstation.

- Have you faced with vandalism, your work being destroyed? Could you tell about such cases and what images have been destroyed?

My work is been attacked and censored by the authorities and fascists, but has never been tagged by graffiti and street artists. This is a great source of pride for me - I do not have to put protective coatings on my work.

If you make art that speaks to the community, if you involve the people that live there, they will protect the work.

- As you worked in many countries, do you see the difference in people’s response to your work? Where do you like to work more?

I work all over the US and internationally. Essentially, although there are cultural differences in all countries, workers are much more internationalist today than at any time in history.

The Internet is home to the greatest international political and cultural exchange that has ever taken place. We have more in common today than ever before. That is why I find a similar response to my work wherever it may be.

- Do you notice a significant rise of interest to social and political graffiti and murals in the US with the rise of protest movements like ‘Occupy’?

Whenever people become engaged in struggle, they immediately turn to the arts to use as a weapon and form of expression. This is clearly happened with the occupy movement, through such things as the people’s megaphone, street performance, sign and banner making, video production, etc.

- There have been fierce debates in our country recently over the issue of the artist’s place in society. There is a dominant elitist view claiming that an artist is above society and should teach it, while ‘old’ social realistic artists claimed that an artist should be with people. Where do you place yourself as an artist?

I am unwilling to accept the position of either the bourgeois society of the employers or the Stalinist Socialist Realism of the bureaucrats.

Artists are workers, and our fate is entirely bound up with the rest of our class. We have a responsibility to our fellow workers that clothe, feed and shelter us. We should oppose elitist concepts for any section of the working class.

At the same time, we need to recognize that we have special training and gifts to bring to our class. I support collective bargaining for artists and training to elevate our skills to the highest levels of professionalism. Being an artist makes you a worker – but being a worker does not make you an artist. (Although I am convinced that every human being is capable of making compelling art).

One of the great things about the Soviet avant guard was their ability to create modernist, challenging art that was understood and embraced by masses of workers and peasants. This was exemplified by such pieces as El Lizzitsky’s ”Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge,” and Tatlin’s Monument to the 3rd Communist International.

- Have you ever made your works illegally – without permission?

Generally, I take great care to attempt to work legally. This is not for moral reasons, but for practical political concerns. As revolutionary activists functioning in the United States, we are subject to pervasive government snooping, frame up operations and victimization. We cannot necessarily afford the self-indulgence of doing street art that might land us in jail when we have critical movements or demonstrations to organize.

It is also important that workers understand you are serious about democratic rights by fighting for your ability to paint in an open political manner.

- You often use images from the history of labour movement and class struggle. There are some points of view claiming that new protest movements should break with the historic tradition and create their own new tradition. Why do you consider history and tradition so important for new generations and modern class struggle?

These two ideas should not be counter posed. We are, in fact, creating new symbols and methods of expression all the time. But it is also important to relearn our real history. Art and politics, like science, is often based on failed experiments. We need to learn from the past so that we don’t repeat the mistakes we have already made.

We have such a rich history of militancy and creative expression. When people are actually exposed to their real history they become inspired to act today. It becomes less of an act of moral witness and more of an act based on believing that we can win.

I am not engaged in political action because I want to feel better. I want to make a revolution–to overthrow corporate capitalism and establish a new world based on human needs. I believe that’s possible because of what I know about the past.

- What can you say about modern American labour movement? Has it lost its great traditions of 1930’s or maybe you see a revival?

All of the pressure that the US ruling class brings to bear on the peoples of the world, all of the weapons that are directed against those who stand up to imperialism – those efforts pale in comparison to the pressure that is brought to bear on American workers.

All of the hideous ideological weapons of capitalism are aimed, first and foremost, at North American workers–to convince us that we are powerless to change society. Every worker must struggle every day, not only to overcome the actions of their employers, but also the leaderships of their own unions and political organizations. It is a heroic struggle that American workers wage on a daily basis.

The struggle of the North American working-class is not being manifest in street demonstrations, but that day is coming. When it does, it is going to blow the minds of the world’s people. The ruling class knows this, which is why they are establishing indefinite detentions and prison cultures that will respond to the rebellious militancy that American workers have so often exhibited in the past.

- Do you have young followers who work in your style?

Hopefully, they will do much better work than me!

- What such a word as ‘solidarity’ means to you?

- Could you wish something to our young street-artists?

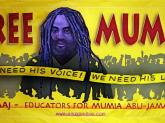

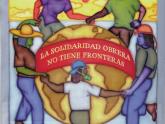

Solidarity is the basic weapon of the working class: Solidarity between workers of all countries. Solidarity between genders and people of every sexual orientation. Solidarity that unites against racism and sexism in all its forms. Solidarity that always speaks to the most oppressed of our class. Solidarity that recognizes the most despised and marginalized workers as our sisters and brothers. Solidarity that reaches into the prisons and dungeons and says to those without hope that we are with you in spirit. Ultimately, that solidarity is our most powerful weapon.

Young street artists (of all ages) must give visual expression to that solidarity. We must put the heart of the working class on the walls. We must be communicators and unifier’s of our class.

We must use our art to organize, agitate, educate and inspire our class to fight and to win.

Original article at: http://liva.com.ua/alewitz-mike.html

-

Історія

Африка и немцы - история колонизации Намибии

Илья Деревянко история колонизации Намибии>> -

Економіка

Уолл-стрит рассчитывает на прибыли от войны

Илай Клифтон Спрос растет>> -

Антифашизм

Комплекс Бандеры. Фашисты: история, функции, сети

Junge Welt Против ревизионизма>> -

Історія

«Красная скала». Камни истории и флаги войны

Андрій Манчук Создатели конфликта>>

RSS

RSS